What if the voice driving your anxiety isn’t irrational, but misdirected?

What if the real threat isn’t failure, but how you speak to yourself when you fall short?

This piece explores what happens when self-criticism becomes a pattern, and how compassion might offer a different path.

🎧 Before you dive in:

At the end of this post, you’ll find a short guided audio exercise. A 10-minute meditation I put together to help you practice the core method directly. Use it to practice to quiet your self-criticism and meet yourself with compassion.

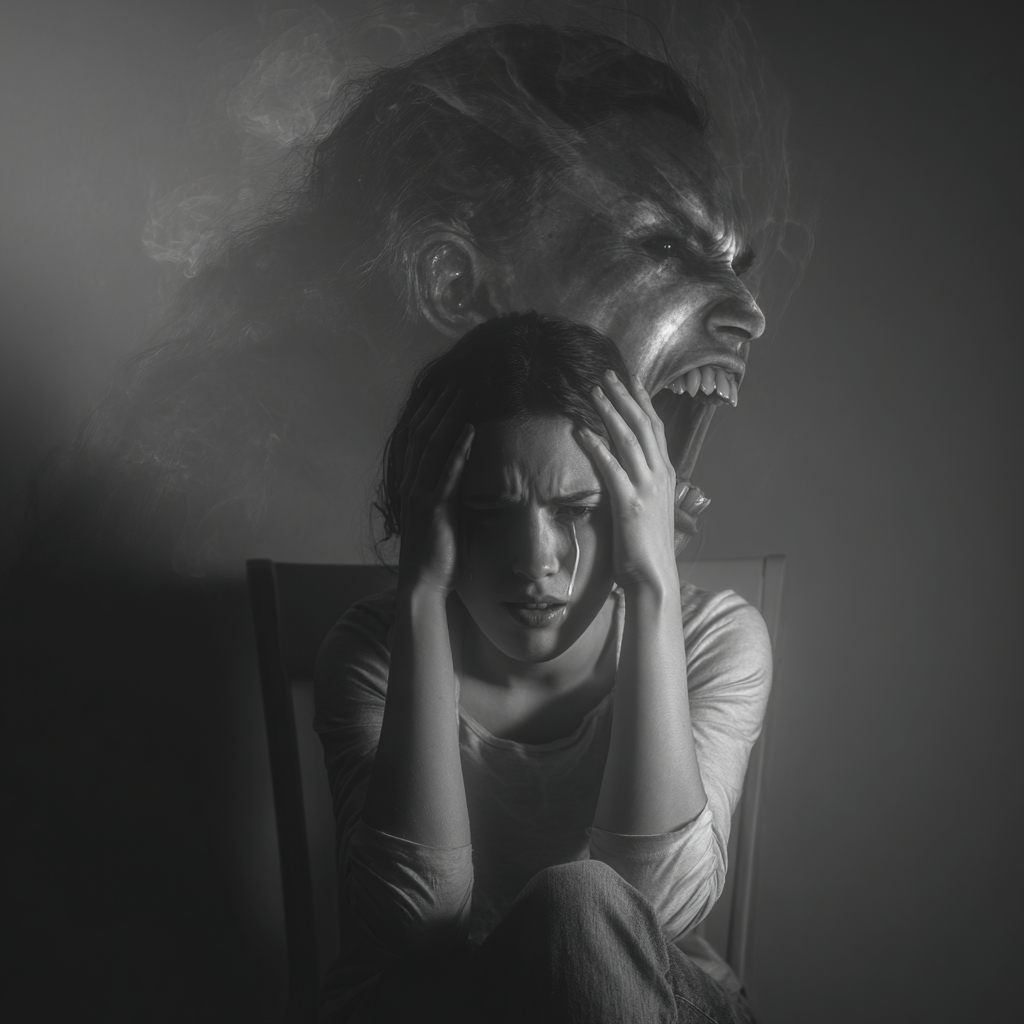

The Threat Within: When Your Worst Enemy Lives in Your Mind

Elisabeth closed the door behind her and turned the key in the lock. She had to be alone. An afternoon, perhaps the whole evening. Hidden, far from curious eyes, strained smiles, yawns and furrowed brows. Right now she wanted no one.

As the silence wrapped itself around her, like icy water tumbling down a mountain stream, she froze—motionless, carved in stone. She just stood there. In the hallway. In her own home, gazing at the furniture in front of her. Yet, another scene lingered before her eyes—the endless rows of red seats filling up with people in suits, the stream of colleagues flooding in from the sides, the lecture hall slowly waking under the harsh light from the spots above. It felt so real. She almost had to remind herself she was no longer there, lecturing. She was home now. Safe, at least in theory, far from the mingling and the chatter, far from the restless tide of human faces.

Slowly returning from her inner vision, losing up, she slipped off her blazer, hung it neatly on a hanger, and grabbed a glass of water before collapsing into the pillows of her bed. Alone. And still—not quite. Something else waited in the room, something that never left her side. The threat within.

Her therapist had encouraged her to meet whatever showed up inside—words, thoughts, images—without wrestling with them. To notice them, let them drift by like leaves on a stream, nothing more than passing shapes in her mind. But it never seemed to work. No matter how she tried to accept, to step back, to loosen her grip, it still felt like being pierced straight through the chest by a blade.

What lived deep inside her skull was a monster. Not with claws or wings or gleaming teeth, but a monster all the same—one that could convince her she was no more than dust, the worst person alive. Like a dark routine, it filled her with shame, flooded her with anxiety, and lulled her to sleep with tears.

For as far back as her memory reached, the monster had been there. Ever present. Ready to strike the moment she handed in a school assignment, sang a note in the choir, played football with her friends on the grass along the old railway tracks, or stood before her colleagues giving a lecture. Always ready with the same relentless magnifying glass, held up to her face. The tiniest slip, the smallest hesitation, was enough to ignite the flame within her and turn her whole world into a pyre. A blaze that couldn’t be extinguished.

As she shut her eyes, still lying in bed, the voice hissed in her skull: “You made a fool of yourself today. You spoke too softly, too loudly, too fast, too stiff. No one was listening to you. And you neglected to explain your slides properly. Most of them had no idea what you were even trying to say. You should have practiced more, pulled yourself together, and stopped looking so damn nervous!”

Like an inner spotlight turned cruel, the voice replayed the lecture she had just given in the auditorium, dissecting each moment with merciless precision. Step by step, mistake by mistake, the monster dragged them out into the open. Every slip, every unclear phrase, every flaw that demanded her shame.

It always began with small jabs—why did you say that, that was wrong… But soon the jabs hardened into insults, then into relentless self-criticism, and at last self-hatred. A blunt hatred that stripped away her sense of self and left only a cloud of anxiety in its place.

For it was here—in her doubt, in her uncertainty, in the gnawing suspicion that she was useless, worthless, an impostor—her anxiety thrived, and the world turned dark. Pitch black.

The Game: The Real Cost of Self-Criticism

Even if it feels that way—especially in the heat of the moment, locked in a dialogue with her inner critic—Elisabeth is not alone. Her story of the threat within, her very own monster is no exception. In fact, nearly one out of five people worldwide are thought to struggle with low self-esteem, and with it, self-criticism—and, in some cases, even self-hatred. Forces that often lead to anxiety, sleepless nights, or depression. In the worst cases scenario, suicidal ideation.

As a clinical psychologist, I can attest to this picture. Many of my patients speak of the same struggle: an inner voice. Not that speaks out loud, but one that makes itself known through thought. Slithering in the darkness, whispering how they should have done better, reminding them how awful they are, how terrible they look, and that they are worthless, even ridiculous.

Unfortunately, symptoms like these are often overshadowed or absorbed by other psychiatric diagnoses such as social anxiety, stage fright, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and so forth. There is simply no official diagnosis for weak self-esteem, excessive self-criticism or relentless self-hatred. Not yet, at least. Still, that doesn’t mean a vast portion of humanity isn’t suffering from just that—a warped, negative image of themselves—and desperately needs help addressing it, beyond acceptance, exposure, and cognitive restructuring, which are common techniques when it comes to social anxiety disorder or OCD.

From early on, within each and every one of us, self-awareness rises unbidden, insisting on being heard. A picture, an idea, of who we really are. Research has shown that some animal species possess some form of self-recognition—they can, in a limited sense, see themselves in a mirror. But humans take it much further. Our self-awareness stretches far beyond body, size, or movement. It’s not just about recognition or memory. We interpret ourselves socially and attach meaning to whatever we say, wear, and whether we succeed or fail. In fact, throughout life, most of us live under an inner magnifying glass, constantly evaluating our behavior, our bodies, our very selves—often in relation to others, and all too often against an impossible inner ideal. Simply put: an Elisabeth 2.0.

While it’s natural to feel some unease in the face of this inner scrutiny, the magnifying glass is not in itself the real issue. Quite the contrary, it can even be useful. The trouble begins only when the inner critic lashes out, punishing us for who we are—or for who we are not. That is when the pain begins. Feedback in itself is seldom the enemy. Without it, life would probably be even harder. But when feedback becomes contempt, that is when the pain truly begins.

Let me explain.

Picture yourself for a second, as the coach of a scrappy football team of ten-year-olds heading into a big tournament. The children want nothing more than to stand as winners at the end, holding the golden trophy. They’ve trained hard for it. That much is clear.

So, you hop on the team bus—the old battle wagon—ride a couple hundred miles across Europe and check in at some hotel. Later that week, it’s time for kick off. Fearless, the kids play match after match on foreign turf, through the group stage and into the knockout brackets. Until, eventually, they face an Italian team that simply can’t be beaten. The kids on the other side of the pitch, dressed in Milan’s colors, play tight, keep possession, turn the game around, and put two goals in the back of the net before halftime. The match, sadly, ends 4–2, and at 50 minutes in, the whistle blows like a gong across the field. From one minute to the next, you are done, the tournament is over.

It’s time to leave the pitch, untie the laces, hit the showers, and head back to the hotel. But before you do, you gather the kids in a tight circle. They look crushed. More than one is crying, devastated. Another hides their face in their hands. It is plain to see: the loss has struck deep. Tears, flushed cheeks, eyes lowered, fixed on the soft plastic turf, as if seeking refuge in the ground itself.

Silence.

In this very instant, watching their faces and searching for their eyes, you—as their coach—are faced with a choice. You could scold them, tear into their performance—blaming them for running too slow, dribbling too little, misplacing their passes, and losing the match altogether. On the other hand, you could take another route—remind them the match was recorded, and that anyone who wishes is invited to watch it later, tonight or tomorrow, to reflect on what the team can do better next year.

But there is also a third option—perhaps the most important one. You can acknowledge and validate their feelings, through your expression, your body language and words. The point is to let them know that it’s okay to feel sad. That it’s okay to hurt. That there is nothing strange about being devastated. In their world, the game mattered. It was real. And because it mattered, the loss was bound to stir emotions.

Even though it may seem that way, the real problem does not arise when the children on the field are struck by sadness and begin to cry. That kind of pain—born of sorrow or despair—belongs to life. It is, in fact, benign. At least as long as we are able to validate our feelings, or have them validated by someone else. The problems begin when we cannot meet ourselves in that pain and assume the role of the self-critical coach, scolding and condemning our performances or ourselves. Like so many people do.

Nor is the problem the coach standing on the sidelines, watching the game, observing each child’s play and drawing conclusions about strategy and positioning in order to improve in the matches ahead. After all, we are allowed to have goals, fight for what we believe in and certainly improve ourselves. No, that’s not the issue. The problem arises when our conclusions are delivered through harsh language, contempt, or ridicule. To put it differently, the problem is words, and how they are delivered. The way we speak to ourselves. That is where malignant pain is borne—the kind that tears us down and drags us into the depths. Unfortunately, a common myth—or rather a misconception—linked to this topic, proclaims that self-hatred or self-criticism renders better performance by keeping us on our toes. On the other hand, if we are kind to ourselves and take care of ourselves, we are most likely going to lose our drive and fail to reach our goals. Of course, this theory has been debunked, over and over again, by multiple papers. Beating ourselves to the ground leads to nothing but poor performance in the long run.

How Validation and Compassion Shift the Mind

For most people, it would be unthinkable to scold the children, to berate their performance right there and then, after their loss—especially when they are already wounded, standing on the pitch with their eyes fixed on the turf, silent, even if the goal was to improve their performance. And yet most of us have no trouble doing exactly that to ourselves—lashing out in ways that generate malignant pain, depression, sleepless nights and long-lasting suffering. Sadly, this is true even for the smallest of missteps, such as failing an exam, missing the bus, saying something awkward among friends, or speaking too quickly during a lecture.

This phenomenon—the difference between how we treat a group of children after a loss and how we treat ourselves when we stumble—has much to do with the way the human brain is hard wired, but also with the cultural ideas we’ve absorbed, often early in life.

Here’s the truth: human beings are not really built to be empathetic or compassionate toward ourselves by nature. In a sense, we are blind to our own suffering, and so we struggle to meet and comfort ourselves in grief, in pain, in those moments when it hurts. Quite literally, we have no eyes to gaze upon our own sorrow.

Our own pain—arising from failure, when we fall short of our goals, say the wrong thing, or lose a match—is experienced from the inside, as an emotional state, a mood, a tangle of thoughts. We can’t see our own emotions from the outside, and that makes all the difference.

When, on the other hand, we see someone else suffer—a human being, an animal, or notice a voice breaking under the weight of pain—the brain reacts in an entirely different way. In fact, watching someone else in pain activates mirror neurons and a very specific attentional system (sometimes referred to as the salience network), simply because the impression reaches us through our senses—our eyes and ears—rather than arising from within ourselves. This in turn triggers a process often called shared coding, where the pain, in a sense, becomes our own. To some extent, it begins to hurt inside us too, and that is where empathy is born—in the sharing of pain. Simply put, as we share their suffering, we are also compelled to ease it, to quiet their pain, as best we can, and that is where compassion is born.

To succeed and ease their distress, the most effective strategy is almost always validation—to convey, “I see you, I see that it hurts”—aside from the obvious practical support like holding someone, bandaging a wound, or blowing gently on a bruise.

Still, validation isn’t just something we do because it feels right, or because it is our duty or obligation. In practice, validation sets off a cascade of biochemical processes within the one in pain. Among other things, it triggers a rise in oxytocin, a hormone tied to safety and attachment. As soon as oxytocin is released, the brain dials down its threat response, in part by enhancing GABA, the braking system that steadies the nervous system. At the same time, the body’s parasympathetic system kicks in: we slip into a vagal state, breathing steadies, the heart rate evens out, and HRV (heart rate variability) rises—a marker of better regulation and recovery. Parallel to this, cortisol levels, the body’s main stress hormone, fall, which in practice means a calmer rhythm and more space for rest. In addition, the body releases endogenous opioids—its own natural painkillers—which ease discomfort and create feelings of warmth and relief.

Apart from the fact that our own pain is processed differently when it arises within ourselves—compared to witnessing someone else in pain through our senses—most of us are also shaped by cultural ideas claiming it is right, even proper, to criticize or dismiss ourselves whenever it hurts, or whenever we are in need. A large part of the global population has simply been taught to be hard on themselves whenever they fail, lose, or fall short. They have been taught to criticize themselves, sometimes even hate themselves, when they don’t live up to their own or others’ ideals or standards.

The process of internalizing these values often begins early on, through subtle dismissals or rejections. At the age of four or five it’s not uncommon to be belittled or brushed aside when you are in pain, whether physical or emotional. Phrases like “Come on, it wasn’t that bad, toughen up” or “Crying won’t help” often escape our parent’s lips. Effortless. Almost automatic.

In sharp contrast, parental warmth and emotional coaching—materializing as a parent comforting a child in pain or helping them make sense of their feelings by labeling their emotional reactions—lead to better emotional regulation and less self-hatred and self-criticism in adolescence and adulthood. But that’s not all. Validation, the simple gesture of sharing the burden, also lowers the risk of relapse in several psychiatric conditions.

Failing, losing, embarrassing ourselves, or falling short of our goals is, in other words, part of life—something no one can escape. But how we handle such experiences, or more precisely how we train our own mind to respond when mistakes happen, is decisive for our mental well-being, both in the short and in the long run.

A Biological Approach to Self-Compassion

Unlike the football metaphor, where the coach decides on his own whether to criticize or validate the children, we as human beings have no such direct choice when it comes to self-criticism, self-hatred, anxiety, shame, or sadness born out of our own thoughts. Hence, it doesn’t make sense to ask yourself—or anyone else for that matter—“why are you criticizing yourself? Why are you so hard on yourself?” Asking a question like this is as meaningless as asking the body why it has developed diabetes, or why it has been struck by cancer. Neither cancer nor diabetes are processes we control. They are not choices we make. The same goes for self-criticism. Self-criticism is generated by our autonomous mind, a part of the brain we have no insight into, and no control over. Hence, we can’t really control it.

That said, none of us are mere bystanders, nor powerless, when it comes to our own body or mind. In fact: most of us can influence the risk of developing diabetes or cancer—by using sunscreen, avoiding cigarettes, steering clear of artificially sweetened foods, exercising, and prioritizing sleep. In the same way, most of us are also able to train our mind to be kinder to itself, to drop the harsh language, drop the insults, and thereby reducing the risk of falling into self-criticism, self-hatred, anxiety, shame, depression, or sleepless nights.

Although much of the mind runs on autopilot—spinning up thoughts and emotions that are pushed into our awareness, whether we like it or not—it’s still possible to influence these processes indirectly. One powerful way of doing so is by training our capacity for self-compassion. Self-compassion has, in fact, been shown in countless studies to ease struggles such as self-criticism, self-hatred, anxiety, and depression, if used correctly, not just as feel-good fluff. In fact, by teaching the autonomous mind to take better care of itself, it’s possible to strengthen our innate affiliation and caregiving system, which in turn helps us get a grip on anxiety—especially when we feel anxious due to something we have done, such as a mistake, or self-criticism, which is far from uncommon.

Moreover: fostering self-compassion quite literally affects biochemical activity in the brain, often by shifting activation toward the medial orbitofrontal cortex, the pregenual anterior cingulate, and the ventral striatum—regions linked to warmth, attachment, and recovery. And just as in the case of validation from another human being, self-compassion increases parasympathetic activity, heart rate variability, while also lowering cortisol levels, and boosting the release of oxytocin and endogenous opioids.

Together, as a powerful potion, these processes are designed to slow down the threat response, partly via GABA mechanisms, helping us slip into a vagal state: breathing falls into rhythm, the pulse steadies, and clear thinking becomes possible again.

Hence, self-compassion is not just a psychological stance, nor is it something you simply owe yourself. Self-compassion activates a biological network in the brain—one that can be trained.

I can still recall the moment I first practiced this strategy, as an intervention in my own life. Obama was still in his first term, gearing up for re-election, while I studied psychology. The Scandinavian summer was brightening up, and I was heading back to Oslo, where I planned to throw myself into a strict running schedule. Then, out of nowhere, disaster stroke. Suddenly, I fell ill. A cold. Not once, but twice in succession. At first, the old machinery of my autonomous mind kicked in, thundering forward like a locomotive—condemning me, accusing me of carelessness, of recklessness, of eating unhealthy junk, of not sleeping enough, of weakness. I felt angry, disappointed. And hardened.

As a defense against the dark arts, I quickly remembered what I had learned that semester and chose to give it a go by practicing self-compassion. Initially, I turned my focus toward the goal itself: exercising, running, training, and the races. In that moment I reached towards what I truly wanted—progress, achievement, the finish line. During the next step in the process, I kept turning inward, leaf by leaf, until I faced the illness itself. The cold. The barrier. What stood between me and my goal. I could feel it. And there, beneath the surface, I uncovered how it truly made me feel. And it wasn’t anger, hatred or even self-criticism. It was something else, something tender, sore. Sorrow. A quiet, aching sorrow. At the heart of it, I was simply sad that I couldn’t run, that I couldn’t practice. It all boiled down to sadness—that was the truth. And with that recognition, the voice of criticism gave way to something softer. Care. Compassion. There was no reason to be hard on myself—on the contrary, what I needed was to take care of myself.

And from that day on, I realized that the only way forward was to find the wound, to name the weight pressing me down. Only in that light could I truly experience my own emotional response, and ultimately turn toward compassion for myself, bringing an end to the inner critic. Somehow, by fixing my inner eye on the feeling, empathy arose, giving rise to compassion — as if I could see my own suffering and awaken the same network within myself that is activated when I see someone else in pain.

Of course, self-criticism doesn’t always have to be as explicit as in Elisabeth’s case. It wears many faces, and it manifests in many ways. For example, it might whisper that we’re not good enough at work, that we’re the worst in the class, that we should have handled that conversation with our friends differently, invited them to dinner, or spoken up in a smoother way. Still, no matter what shape or form our inner criticism takes, it often triggers anxiety—which, at its core, operates like a fire alarm.

Here’s how it works: much like a smoke detector, built to warn us of an impending disaster and help us escape blazing fire or deadly smoke, anxiety is in part designed to help us avoid social humiliation, exclusion, and loneliness. That’s why anxiety is so easily triggered by criticism, whether it comes from another person—or from within. Criticism is the shadow that falls before the storm.

Hence, anxiety as a warning signal doesn’t wait around. The moment criticism leaves the autonomous part of the mind, or is carved into us by someone else, and reaches our consciousness, the alarm goes off. Criticism is just like smoke curling upward from a toaster, winding its way into a detector on the ceiling, which in turn sets off the alarm.

No hesitation, no second guessing.

But here’s the thing: criticism and anxiety are not your enemy. I know, it sounds weird, but hear me out, criticism matters—it actually helps us navigate the social world, keep relationships intact, and prevents us from being pushed to the margins. The same goes for anxiety. In many cases, anxiety is a useful signal, a feeling that lets us look ahead and spot threats before it’s too late. Anxiety signals us to hide, or sharpens our focus on a path that might help us escape what’s ahead.

The real problem is that our inner alarm system can’t distinguish between genuine, warranted criticism and the imagined, fictitious world inside our own mind. The system treats both sources as equally valid, which, unfortunately, they are not. We are rarely a worthless speaker, even if others happen to be better at presenting than we are, or someone in the audience falls asleep during our lecture. Moreover, we are rarely unintelligent, or undeserving of our spot in school, just because we failed an exam. The truth is that we probably didn’t study enough, or studied the wrong material. That’s why we failed—not because we’re stupid. And yet self-criticism is quick off the mark, always ready to claim one thing or another, whether it holds any truth or not. And we are forced to listen—and to feel. And sometimes even dive into the abyss.

Rewiring the Mind: The Inner Avatar Exercise

Though it carries a fair share of complexity and demands real effort, there is one exercise I highlight above many others when it comes to disarming self-criticism and fostering a more compassionate mind. Welcome to your Inner Avatar.

To get the most out of this exercise, I strongly recommend that you read through the instructions first, and then listen to the guided meditation.

Your first task is to create an imaginary place in your own mind. A place built on one simple rule.

You should feel—or at least believe—that you are calm here, safe from threats and worries.

It can be anywhere: deep in a forest, high among the mountains, at the beach, in your own home, or traveling in a spacecraft toward another dimension. The choice is yours. If picturing yourself alone doesn’t feel safe, allow someone to be there with you. In some cases, even an animal will do

Once your place has taken form, it is time to move on to the second step. Try picturing an avatar, a being of your own design. Choose its appearance—its colors, size, and shape. What you can’t decide, however, are these three attributes that are inherent to the avatar.

- However it appears, your avatar has lived hundreds of lives before this one, and has seen almost everything there is to see: humanity on the savannah, our endless migrations to distant continents, the hunger, famines, and nomadic life, the rise and fall of the Egyptian empire and Mesopotamia, the grandeur and collapse of Rome, the long medieval night, Columbus crossing the Atlantic, the world wars, the concentration camps, and all the way in to the 21st century. The avatar has witnessed human suffering from every angle, and it knows what it is to be human. It knows none of us chose to be here, nor did we choose our genetics, upbringing, or our pain.

- Beyond this near-eternal life, the being is not afraid to take care of you whenever you need it. It remains always present when you speak of the hard things in life—at least if you allow it to be there.

- And last but not least, the being doesn’t judge. It cannot judge. It knows what it is to be human. Hence, it accepts all of who you are, and never criticizes.

When you are ready—when you have created a being that has lived nearly forever, that cares for you, and that never judges—it is time to receive it in your very own place. Try to see it as it emerges, as it steps into your safe place. Take a good look. Adjust, reshape, if you wish.

From this point on, I want you to write a letter to yourself every week for at least eight weeks in a row. But instead of writing from yourself to yourself, in the format of a diary, I want you to imagine writing from the perspective of your avatar. In other words, your avatar is the one holding the pen, not you. What is more, go on to imagine that the avatar has been with you during the past week. Wherever you have been, it has been there, watching you, felt your feelings and heard your thoughts. And from all you have endured—the hardships, the pain, the fear, the wounds—it now writes you a letter devoted entirely to validation.

Begin by describing a situation—something you experienced, something you were part of. Describe the situation as fully as you can, then move on to your own response and interpretation. Write down how you felt, what mattered to you and how you made sense of it. Then move toward validation. And here comes the challenging part: validation is not about saying it’s okay to criticize or hate yourself. Validation is more of a reassurance—telling yourself that it is okay, not strange at all, that you felt sad when you didn’t get the promotion, when you failed the exam, or when you missed a few notes during the performance. Validation is about recognizing the situation, your response, and affirming it—not judging yourself, not expressing disbelief or criticism. A good way to begin is with the wound, with the vulnerable part, and then continue with: it is okay, it is not strange that you felt scared, or sad, or hurt, or disappointed when…

The mistake most people make is falling back into old patterns, validating aggression or criticism instead. They might write: it wasn’t strange that I got angry and punished myself, or it’s only natural that I felt worthless. If you end up here, go back and think of the football team, the children, and the game. Neither you nor the avatar would ever say to them: of course you lost, you’re terrible. Instead you would likely gather them up and affirm them by saying: I understand that you wanted to win, I understand that the match mattered, and that losing hurts. And it’s okay that it hurts. Anything else would be strange.

The important thing is to find the vulnerable feelings: shame, anxiety, fear, pain, sorrow or disappointment. Those are the feelings that matter. Not anger, criticism, hatred, or contempt. Compassion is fostered out of something that hurts—not out of arrogance, criticism, or hate. I often tell my patients that it’s hard to be angry with someone who is crying. Of course, that’s true, with some caveats, yet the vulnerable—the part that hurts—often evokes empathy. And that is precisely what this exercise is about: finding the wound inside you, and in doing so, awakening an empathy and compassion you never thought you had.